Prudential Building, c. 1933. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey.

Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the history of best sellers, exploring the circumstances that might inspire thousands to gravitate toward the same book and revisiting well-loved works from the past that, due to a variety of circumstances, vanished from the conversation after they peaked on the charts. We are also publishing a digital edition of one of these forgotten best sellers, Mary Augusta Ward’s 1903 novel Lady Rose’s Daughter, with a new introduction, annotations, and an appendix. To read more about the project and explore the other entries in the series, click here.

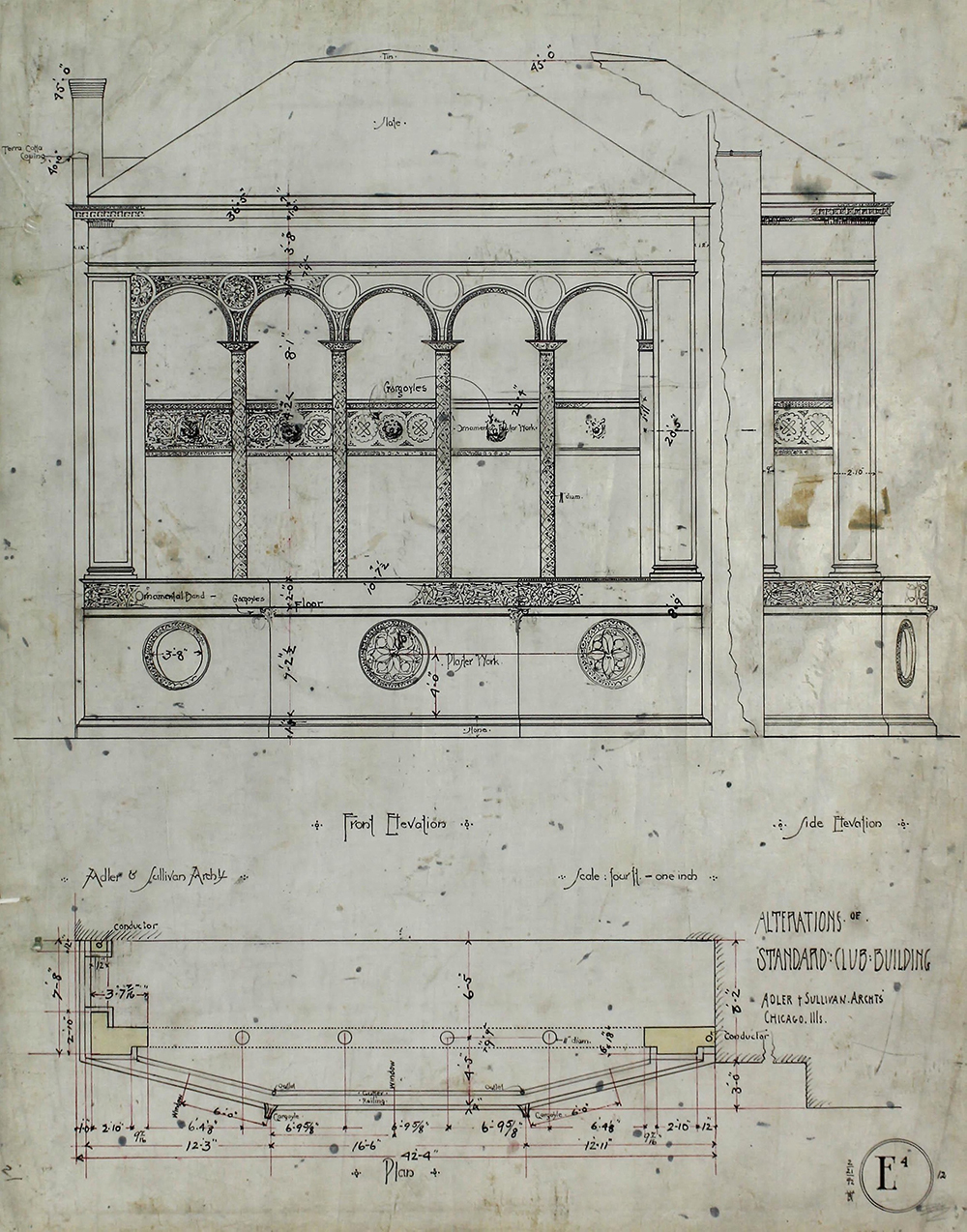

We owe architect Louis Sullivan for one of the catchiest modern dicta on making things: that form should follow function. A pioneer of the steel-frame skyscraper—responsible for the Prudential (later Guaranty) Building in Buffalo, New York, and St. Louis’ Wainwright Building, both prototypes of the modern office building—and a forefather of American modernist architecture, he saw patterns in nature and felt that urban design ought to follow suit. Acorns are made to grow into oaks. Rivers are made to run. A department store should be made to welcome city dwellers and entice them to buy something. “Whether it be the sweeping eagle in his flight or the open apple blossom,” he wrote, “form ever follows function, and this is the law.”

People, generally speaking, gravitate toward pithy phrases and simple rules, even just to end up disagreeing with them. So it’s no surprise that “form follows function” has become a mainstay of Sullivan’s legacy. He debuted the idea in an 1896 piece for Lippincott’s Magazine, “The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered,” in which he outlined the most important considerations for designing the exemplary office (the entrance ought to catch the eye; rows of identical office cells are fine). In 1901 he published a set of fifty-two essays, Kindergarten Chats, which further expounded on the tenets underpinning his idealistic architectural vision. Addressed to young architects, the essays appeared over the course of a year in the Interstate Architect and Builder. In 1918, with some encouragement from friends and colleagues, he recast the essays as a book aimed at curious laypeople in addition to practitioners. It was first published in 1934, a decade after his death.

Kindergarten Chats, Sullivan writes in the 1918 foreword, “is free of technicalities, is couched in easy dialogue form, and its doctrine should be intelligible to all.” The book takes the shape of an extended conversation between a recent graduate of architecture school and a more seasoned—and stubborn—master of the craft. The educator is no doubt modeled on Sullivan himself, a notoriously difficult person whose students included Frank Lloyd Wright, his most famous pupil. The guidance Sullivan wishes to impart is not at all technical—he is unconcerned with teaching his student about the finer points of drafting blueprints and constructing skyscrapers. He’s teaching a worldview instead. “Every building you see is the image of a man whom you do not see,” Sullivan tells his pupil. “The man is the reality, the building its offspring.” In short, you are what you make. If architects wish to build beautiful (and functional) buildings, they must first understand certain things about themselves.

When Sullivan first wrote the essays, he had recently concluded the most productive years of his architectural career: between 1880 and 1895, he designed 256 buildings in his famed partnership with Dankmar Adler, among them the Chicago Stock Exchange building. In the next two decades, he would slowly fall out of favor—and into debt. By the time he revised the text in 1918, the world looked entirely different than it had during his Gilded Age golden days. “The present world tragedy will, at its ending, call for a new valuation of human power, a new and clarified social view and vista, a new illumination of the basic nature of democracy as contrasted with its merely political aspect,” he wrote in July of that year. World War I was drawing to a close, and an influenza pandemic would soon overwhelm the globe. Given that “nothing more clearly reflects the status and the tendencies of a people than the character of its buildings,” it would be the job of young architects, and young creators more generally, to remake society in their own image, using or abandoning the advice of those who came before as seems fit.

And isn’t that the function of a good guide? Not to be all-seeing or to stay current but to plant an idea that sticks. To impart a lesson, rule, or pithy aphorism that parlays new forms for the same functions every time you come back to it.

If we’re taking Sullivan at his word that form follows function, the structure of Kindergarten Chats should tell us exactly what he’s trying to accomplish. The function: learn to think anew by returning to kindergarten. The form: step-by-step lessons from an experienced guide.

How-to books, guides, and teaching texts have long been staples on library shelves and best-seller lists. Dale Carnegie taught more than thirty million eager readers how to win friends and influence people. Robert Atkins preached the virtues of a low-carb diet. Marie Kondo changed how many of us think about what we own, training hoarders and pack rats to “discard anything that doesn’t spark joy.” I’m willing to bet that most readers of these works don’t wind up adopting the habits or codes of conduct their writers preach for the long term. The point of the book is to get the catchphrase stuck in your head, not to get you to stick to the diet. Kindergarten Chats is odd and esoteric, a text meant to teach architects to see and build rather than solve a problem like clutter or weight loss. But Sullivan’s book, like these guides, is built on a premise so legible it stays with you whether you want it to or not. “It is somewhat the fashion, in modern thought, to make simple things complicated,” Sullivan tells his student in Kindergarten Chats. Books that do the opposite, he seems to suggest, are the ones with staying power.

Ultimately, the premises of Kindergarten Chats are so simple it almost seems silly to say them out loud. You must make something with its intended use in mind. The things you make are a reflection of who you are. Set aside overblown ideas like the ones taught in design school and instead focus on the basics. Will readers come away with the tools necessary to design a skyscraper? Certainly not. Instead the book maps the etymology of an idea for a student who must figure out how to incorporate new information into his own burgeoning practice.

Some critics saw Kindergarten Chats’ simplicity as its central problem, however. As the author Paul Goodman and his architect brother, Percival, noted in a 1942 essay about Frank Lloyd Wright, the vector for many of Sullivan’s brightest ideas, “the only thing that prevents the Kindergarten Chats from being a major classic is—that there is no concrete discussion of architecture in them.”

Outside the realm of architecture students and modernism enthusiasts, Kindergarten Chats never gained the mainstream traction Sullivan hoped it would. But the ideas he outlined have retained their potency far beyond the book’s comparatively meager readership and long after many of his once-iconic buildings had been torn down. How-to books are written to be distilled, after all. Their influence marks their success. With Kindergarten Chats, as with so many books of its kind, the central idea was the true best seller, one that would persist through various interpretations and applications even as the book itself quickly fell into obscurity.

All writers run up against the chance that their work won’t withstand the test of time. Sullivan’s reliance on presumed universalities puts him at greater risk. And in both 1901 and 1918 he was writing from a global crossroads, all but ensuring that his work would seem dated to readers encountering the work not even a generation later. Sullivan’s narrator in Kindergarten Chats, an unnamed version of the architect himself, knows this is inevitable. Including his student’s commentary—acceptance, confusion, enthusiasm, pushback—serves to illustrate that. All pupils get to make the choice to internalize some lessons and ignore others.

Sullivan was hardly the first author to build a book around conversations between a student and a teacher. Look no further than Plato. As in Socratic dialogues, Kindergarten Chats follows the winding path of discussion, argument, reflection, and, more often than not, ample head-scratching. On the subject of a New York office building, for instance, Sullivan’s student pushes back against a lengthy diatribe from his teacher:

“You choose to be brutal again.”

“The building is so all the time.”

“But it is the work of an eminent architect, I am told.”

“Then they are both ‘eminently’ unsavory.”

“Have you no regard for a fellow practitioner?”

“None. I have regard only for our art. Moreover, this architect, this ‘eminent’ architect, save the word, has shown no regard for you or for me or for any other passerby. Why then should I regard him?”

The narrator’s rant continues apace, prompting his pupil to ask at one point, “Aren’t you laying it on pretty strong?” Throughout the book, the interlocutors spend much of their time squabbling. Despite the teacher’s forcefulness, the questioning leaves it unclear who is actually right.

Writing a teaching text requires some degree of authoritativeness by definition. Most how-to books and guides make ample use of the second person. In advice columns, an all-knowing writer offers words of wisdom in response to a letter from someone seeking help. A commanding and assertive voice is, to some extent, a prerequisite. True to form, Sullivan’s narrator often defaults to grand, flourishing pronouncements—the verbal equivalent of the skyscrapers he built. He opines that “to know your art you must broaden your sympathies.” He proclaims New York City the exemplar of “gigantic energy gone wrong.” His references to the natural world can be particularly florid, as when he proclaims that pessimism is a “winter which falls upon the mind when sympathy has flown.”

In Kindergarten Chats, the active participation of the young architect is a necessary counterbalance to Sullivan’s fussy and ostentatious teacher. The dialogues create a reading experience that doesn’t feel entirely top-down. The young architect still gets to do his own interpretive work, and so can the reader.

Around the same time that Sullivan was reworking his essays into the Kindergarten Chats manuscript, E.B. White—then just nineteen or twenty—enrolled in professor William Strunk Jr.’s English 8 course at Cornell. One of the required readings was a small guide to composition called The Elements of Style, written and self-published by Strunk. Little did White know then that some forty years later he would be revising his professor’s work for mainstream publication. What was once a handbook for Cornell students became one of the enduring best sellers of the twentieth century.

The Elements of Style is more of a how-to book than Kindergarten Chats. The text is less meandering and is organized into numbered lessons, many accompanied by straightforward examples. But Strunk and White’s aim, like Sullivan’s, is universal and astonishingly simple. After all, doesn’t good composition boil down to being a clear communicator?

Omit needless words.

Where emphasis is necessary, use words strong in themselves.

Style is the writer, and therefore what you are, rather than what you know.

These guidelines are useful even if the only thing you’ve ever written is a three-line email.

Much as Strunk and White’s classic proves useful to anyone who wants to communicate clearly, art teacher Betty Edwards’ 1979 book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain rose to prominence as a textbook for those hoping to see and make art—and to understand their own creative faculties—in a new light. Edwards uses a series of art exercises (draw your hand, draw a profile portrait) as an opportunity to refocus her students’ eyes and hone their powers of perception. Her instructions are rooted in the idea that anyone wishing to draw well must learn to shift between the left and right halves of the brain. “Learning to draw is more than learning the skill itself,” she tells her readers. “By studying this book you will learn how to see.” Indeed, Edwards went on to build a franchise rooted in teaching people to think and perceive with the right side of the brain.

Read together, these two slim, influential books and Sullivan’s Kindergarten Chats are comrades in arms, form, and function. They also share many of the same flaws. Each book is, in its own way, outdated—a time capsule from a bygone era—and doctrinaire. The distinction between left- and right-brain thinking that Edwards built her lessons around is regarded by most as unfounded pop science. Strunk and White’s rules are overly rigid and out of keeping with many modern conventions—I’m sure I’ve broken dozens in this essay. Sullivan, for his part, is pompous and hypocritical. His self-importance and circular lessons frustrate his student so much that he takes a trip out into the wilderness in the middle of Kindergarten Chats to process his teacher’s lessons and reconnect with the natural world from which his designs are meant to originate.

After his breather in the countryside, Sullivan’s student returns ready and willing to soak up the rest of what his teacher has to offer. The pair persists through lingering disagreements and confusions, and after some time together Sullivan anoints his student ready to venture out into the world. “Now begin,” the book ends. Once again, form follows function. Kindergarten Chats concludes at the beginning because Sullivan—himself a former rebellious student—knew that teachings are a starting point and not a destination.